| Accueil/Home | Radio Blues Intense | Sweet Home RBA! | All Blues | Dixie Rock | Carrefour du Blues | Interviews | Liens/Links | Contact | Powerblues |

The Days Of Love & Blood

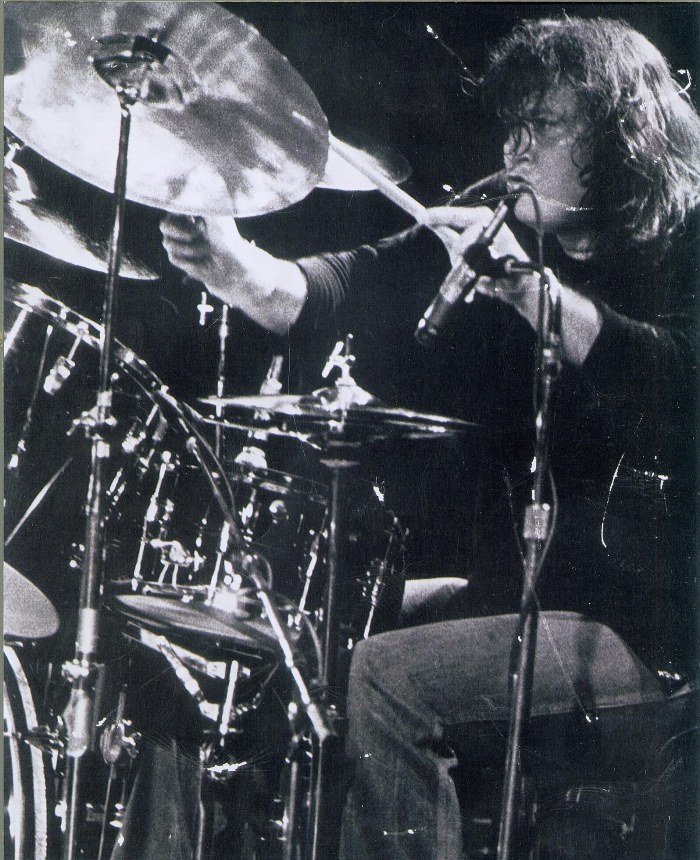

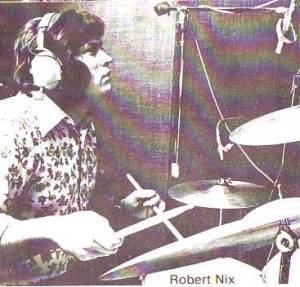

by Robert Nix

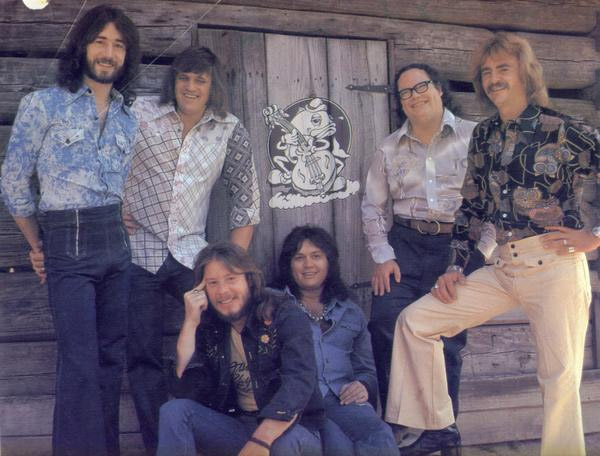

Candymen

Atlanta Rhythm Section

Atlanta Rhythm Section

Original version of the text published in Bands Of Dixie #64 (September - October 2008)

If the Atlanta Rhythm Section is still alive today, it must be said that its star has a bit fallen down since the golden age of the seventies. To talk of these glorious days, we met Robert Nix, his drummer, that one who didn't want to live through the decline of the ARS and left it at its fame. The career of Robert Nix doesn't stop there since he has been, for example, playing for Roy Orbison with the Candymen; he rubbed shoulders with the biggest musical names and was close to Ronnie Van Zant. Before the interview itself, in the next issue, we offer you "The Days Of Love & Blood", a text penned by Robert Nix and which is the summary of a book he's currently writing.

It was the mid-sixties in Jacksonville, FL. I was eighteen and playing drums with a local band at a club called the Golden Gate Lounge. There was a large commotion at the entrance to the lounge. I looked up to see a man with jet-black hair and even darker sunglasses and it was 12 o'clock midnight. He came in with his band to see this drummer they had heard about. The drummer was me and the man in black was Roy Orbison, the number one male pop/rock vocalist in the world at the time. He listened to me and my band play for fifteen minutes. Then Roy Orbison asked me, Robert Nix, to join him and The Candymen on a tour of England. I gladly accepted the offer. This was really the start of my career in the music business.

After a second tour of England, Ireland and the continent of Europe with Roy Orbison, we flew back first class to New York. I was sitting with Roy and I noticed these two guys sitting behind us. It was Otis Redding and Phil Walden, Otis' manager. Otis and I swapped seats so he could talk with Roy. It was unbelievable! I had the two big O's sitting together for the first and last time. They autographed my plane ticket, the two big O's in black and white. These were the two greatest singers on earth at the time. I started a friendship with Phil Walden that would intertwine with my life for the next thirty years.

Later on, when The Candymen were recording an album in Atlanta, I went to the Marriott Hotel with a disc jockey friend of mine, Johnny Bee. We went riding around with Otis Redding. Otis told me he had a song he had written for us. He started beating on the dash and shaking the whole car as he sang "cos, cos, I'm a love man." Later, Otis scored a big hit with this same song.

After touring England and most of the continent of Europe, I returned to Jacksonville. The Classics IV, The Bitter Ind., The Second Coming, future members of The Atlanta Rhythm Section and several other rockers like Lynyrd Skynyrd and the Molly Hatchet Band were beginning to eat, sleep and drink rock 'n roll. Other bands like Blackfoot would soon follow. Southern rock was in the womb and Jacksonville was the mother.

While playing with Roy Orbison and The Candymen, we would play the most unique show packaging I've ever heard of. We did a Texas tour once with The Four Tops, BJ Thomas, Sonny James, Willie Nelson, Rick Derringer and The McCoys and a host of others. It was crazy but fun! I remember in San Antonio one night Roy said, "Big Bob come with me to the show early. You are going to be a great songwriter and I want you to see someone who writes crazy songs, but he's one of the best." He had no band just a guitar. He had short hair, wore a suit with a string tie and was magnificent. He was Willie Nelson. He blew me away. He and Roy Orbison had an unbelievable impact on me as a songwriter.

When I wasn't touring with Orbison, we, The Candymen, would play clubs and concerts with bands like The Allman Joys all over the South. I knew Duane and Gregg had something special even then. As time moved on, The Candymen got a record deal besides playing with Roy Orbison on the road and in the recording studio. It was a heady, euphoric time for me. We were hanging out with The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, Graham Nash, Jeff Beck, Rod Stewart, Tom Jones, Jimmy Page, Jimi Hendrix, The Yardbirds and touring all over the world. I was in LA playing the Whiskey-A-Go-Go hanging out with Stephen Stills, Neil Young and Dewey Martin of Buffalo Springfield. Gregg Allman was charging cigarettes and liquor to my room because he was struggling to make it with his West Coast band, The Hour Glass. In the meantime, Duane was in studios (Muscle Shoals and Miami) recording with Wilson Pickett and Aretha Franklin. Wilson Pickett recorded The Beatles song "Hey Jude" at Duane Allman's insistence. Aretha did "The Weight". Later, I was in Jacksonville to discover Gregg, Duane and company were crashing above the R&R Liquor Store on Main Street. It was a funky old apartment with nothing but mattresses and music. This was the real beginnings of Southern Rock.

The Allman Brothers Band was born. Duane next recorded Derek & The Dominos with Eric Clapton. Eric asked Duane to be a permanent band member. That's when Duane replied, "No, man, Gregg and me and the brothers got our own fish to fry." About this time, we, The Atlanta Rhythm Section, were a major studio band. We played on all the records in Atlanta. We had great commercial success making records and writing the songs for a lot of different artists (Joe South, Dennis Yost and The Classics IV, Billy Joe Royal, BJ Thomas, The Tams). It was successful but we weren't fulfilled as musicians and artists. Someone suggested we make our own records. We did, and we became The Atlanta Rhythm Section.

About this time an old friend from New York moved to Atlanta and seeing the potential there started his own record company with MCA distributing for him. His name was Al Kooper. His label was Sounds of the South. Our studio, Studio One, was where everything was recorded and the rest is history.

Al signed another Jacksonville band of rowdies, The Lynyrd Skynyrd Band. Al Kooper and Ronnie Van Zant asked me to play on the song "Tuesday's Gone" and my friendship with Ronnie began.

Ronnie was tireless. He would record all day with Skynyrd and Al Kooper. Then at night he would hang with us while we were doing our project. One night while watching us rehearse, Ronnie said, "Damn man, you' all are the best band I've ever seen! Ya'll gotta take it to the people." Later on, we got that chance. We opened for Skynyrd and what a ride! We toured all over the south together. I remember Mobile, AL at The Coliseum and Ronnie asked me to go out on stage and bring the band back for an encore. The place was going nuts. Ronnie looked over at Allen Collins and said, "Alright, Allen, you hear what song they're hollerin' for. It's "Free Bird". Get your ass out there and kill 'em." It was what I imagined it must be like in a locker room at the Super Bowl.

During this period, we got tired of being The Atlanta Rhythm Section opening for Marshall Tucker or Charlie Daniels or whoever. We loved them but we were ready to headline. We decided to do what we knew best : record a hit single to be culled from an album. This would obviously up our chart status, our record sales and popularity on the radio. So Dean Daughtry, our keyboard player, me and Buddy Buie, our manager, went to a little cabin on Lake Eufaula, AL and wrote the hit single, "So In To You." It wan an overnight smash. Our record sales soared. The album went gold immediately. We went from $3,500 a night to $35,ooo plus a percentage per show. It was definitely what the doctor ordered.

Later on we played The Capital Theatre in Passaic, NJ. The lineup was Lynyrd Skynyrd, The Atlanta Rhythm Section, Eddie Money and .38 Special. This was the last date of a tour we had been on with Skynyrd. I rode to the show in a limo with Ronnie Van Zant and Gary Rossington. Ronnie said he wanted to talk to me. Ronnie Van Zant was a rockin rollin', hell-raisin', son of a gun, but when it came to takin' care of business, he got real serious. After this show, The Atlanta Rhythm Section would go on to Portland, Maine and start a headlining tour of our own. The opening act was .38 Special. Ronnie grabbed my arm and said, "Alright Robert, look me in the eyes, Skynyrd helped ARS, now it's payback time. Nix, you better watch out for Little Brother's Band!!". To the world, they were .38 Special, but to Ronnie Van Zant, this was his brother Donnie's band. .38 Special didn't really need much help with anything. They kicked ass on stage. They went on to have a string of Top 40 hits and multi-platinum album successes. .38 Special is a touring band to this day.

We toured endlessly with all of the southern rock bands. There was Wet Willie with the multi-talented Jimmy Hall. I remember one night in Thibodeaux, LA; he jumped out on stage with us and jammed on harmonica and sax. It was a very hot happening. The crowd went crazy.

The Charlie Daniels Band was always a great live band that made great records. Charlie has many musical gifts, but I love the way he writes his songs. On the road, I would always walk up to the back of the stage where their very hospitable road manager, High Lonesome, always reached into a big anvil case and handed me a bottle of Crown Royal whiskey. I really enjoyed those times. I guess you could say I received the "royal" treatment.

I loved the Marshall Tucker band doing their hit song "Can't You See." I thought Toy Caldwell was a very gifted, original and unique singer, songwriter and guitar player. On the road, sometimes it would get a bit routine. Sound check in the afternoon, go back to the hotel, get ready for the show, take a limo to the hall, hang out in the dressing room backstage, talk to the disc jockeys and the press, drink your favorite poison (Jack Daniels, champagne, Crown Royal or beer, maybe some of everything for stage fright). But when a band like Marshall Tucker went into a song like "Can't You See", it was anything but routine. It was southern rock magic at its best. I always found myself sneaking out to the stage to get close to the action. This was definitely a hot time in Dixie.

We had a major joke played on us after we wrote and recorded "Imaginary Lover". It seems that a promotion man at Polydor Records and a disc jockey in Dallas, TX, took our record and speeded it up from 45RPM to 78 RPM. It sounded exactly like Stevie Nicks and Fleetwood Mac! Somebody in LA gave it to Mick Fleetwood and told him Stevie Nicks was with another band. He was not real pleased until they told him the real story. This would have been real funny but somebody started playing it before the real version was released. I remember taking bottles of brandy and champagne around to the disc jockeys everywhere straightening out this predicament. "Imaginary Lover" went on to be a gigantic hit single from the platinum album "Champagne Jam." Rolling Stone magazine thought this story was newsworthy. They wrote a great article about this joke! It even ended up being great press for us!

We started headline more and more. When we did open, it would be a sandwich-type situation with someone like The Rolling Stones in a stadium with 80,000 people in the stands. We played major stadium dates after this chart success. I remember one afternoon playing Mile High Stadium in Denver with Skynyrd, Heart, Foreigner, Dickie Betts, The Outlaws and several other acts in front of 78,000 people. We came offstage and with a police escort, we were whisked away to a waiting jet for Calgary, Canada. That night we played in another sold out stadium with Alice Cooper. One of the craziest dates we ever played was in St. Louis at Beal Auditorium with KISS on Halloween night. Imagine that! After this period of total euphoria, things started getting dark. There was lots of alcohol, drugs, sex and rock 'n roll. There was the death of Elvis Presley and the crash of Lynyrd Skynyrd.

It was a terrible time for me personally because I was totally an Elvis freak and had become very close with Ronnie Van Zant. I knew Ronnie had been killed even before his wife Judy did. I had a friend who knew a neurosurgeon in Jackson, MS, who called and told me about the death victims in the crash even before family members knew. This is mentioned in the book "Freebirds (The Lynyrd Skynyrd Story)." I called Judy and she said she thought Ronnie had made it. I couldn't bring myself to tell her what I knew was the truth. Eventually I tried to help Judy as much as I could. I even bought she and Ronnie's estate on the St. John's River in Jacksonville. She has since become a very savvy and successful lady in several ventures, including a memorial park to Skynyrd and The Freebird Foundation to help with scholarships and other beneficial endeavors.

We first met Jimmy Carter when he was the Governor of Georgia. He was very accessible and loved our kind of music. Later on, during his run for presidency, we helped with a lot of other southern rock bands to raise millions to help with his campaign. President Jimmy Carter reciprocated by inviting The Atlanta Rhythm Section to perform on the South Lawn of the White House. It was October 1978. This date was also important because the Camp David Peace Accord was signed. I'll never forget that Friday afternoon we were doing a sound check on the lawn when President Carter landed in Marine One, his helicopter. He was all smiles and very excited. He walked over and greeted us and said he would see us later that night at the concert. He introduced us by saying, "The Atlanta Rhythm Section and I have a lot in common, when we both started out, all the critics and commentators said we would never make it." He then spread his arms around us and laughed and said, "But here we are!" The crowd of congressional members and their families, the press, radio and television went wild. It was a moment I'll never forget. Later we hosted TV's "Midnight Special". Wolfman Jack introduced us by showing the video of us at the White House with President Carter on national television.

We had the distinct honor of being the only rock concert to have ever preformed on the White House lawn. That is, until Secretary of the Interior, James Watts, under President Ronald Reagan, would not allow a July 4th concert at the Washington Monument by The Beach Boys. He said the Beach Boys would bring the wrong element to such an American symbol. Funny, I always thought of "Beach Boys' music" as very American. When Nancy Reagan heard about this, she was very pissed off. She invited The All American Beach Boys to play on the very American South Lawn of the White House. So now we share the honor of playing a concert on the South Lawn of the White House with The Beach Boys. Thanks a lot Secretary Watt!!

We played many stadiums and outdoor festivals during the next few years. They were all great for different reasons, but one was the Granddaddy of them all. It was 70 miles outside of London, England at an old castle. The lineup was Genesis, The Atlanta Rhythm Section, Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers and opening act, Devo (they were pummeled with whiskey bottles and rotten fruit). I actually felt sorry for them. There were 205,000 screaming fanatics, a sea of blue jeans on a beautiful day, with an old English castle in the background. When we were performing, all you could see were Confederate flags waving everywhere in the middle of England. It was a real culture shock, mainly for us!

Another highlight of my life was when a good friend of mine, Pepper Rodgers, who was then a southern rock music lover, head coach at Georgia Tech, invited me to bring my band and do a major concert at Grant Field Stadium. Georgia Tech had always been a very conservative school. We blew their minds when we played in front of 73,000 people a the "Champagne Jam." Every artist you can imagine wanted to be on the show and we were headlining in our hometown that we had named the band after. The Atlanta Constitution treated us very well when we woke up on Sunday morning following the Saturday concert with a photograph of us on stage, hands joined in the air victoriously. The headline read, "Atlanta belongs to Rhythm Section." It was an amazing feeling.

Through all the thousands of shows, millions of fans, awards for songs, multi-gold and platinum records, too many music friends to mention, it's been quite a journey. In 1978, we played 262 gigs, wrote all the songs for The Champagne Jam album and recorded the record all in one year. I didn't really see my family except 2 or 3 times every couple of months. Many sacrifices were made for a dream. I lost a lot of friends along the way. Who would believe that something as simple as making music could be so complex and dangerous? Who would believe that a young musician, songwriter, record producer, rock star entertainer could start out with managers and publishers, just one big happy family, dreaming together only to end up fighting over copyrights and likeness usages like mortal enemies.

Looking back, those days in southern rock were the days of love and blood.

We started out, we had such good intentions,

And there was no doubt we believed in our invention.

We sang our songs and everyone followed.

It was so deep to end up so hollow

We planned a happening, but it ain't happening like we planned

And there was a time, yes, I remember it well,

And I can't forget how it was heaven and it was hell.

We were just children making music in the mud

Changing the world in The Days of Love and Blood.

We planned a happening,

But it ain't happening like we planned.

(From the song, "The Days of Love and Blood"; written by Robert Nix, Alison Heafner, and Rick Christian).

And there was no doubt we believed in our invention.

We sang our songs and everyone followed.

It was so deep to end up so hollow

We planned a happening, but it ain't happening like we planned

And there was a time, yes, I remember it well,

And I can't forget how it was heaven and it was hell.

We were just children making music in the mud

Changing the world in The Days of Love and Blood.

We planned a happening,

But it ain't happening like we planned.

One thing for certain, southern rock will never die. It can best be summed up in the words of a song called, "The End of the Line".

I remember when Elvis died,

And Van Zant went down,

Everybody said, "Rock 'N Roll is dead".

But it was only heaven bound.

Yeah, they thought it was over.

They felt left behind,

But oh it ain't the end of the line.

And the road goes on forever

And the light will always shine

And the song is never ending.

You will never reach the end of the line.

(From the song, "The End of the Line: written by Robert Nix, Alison Heafner, and Wayne Perkins)

And Van Zant went down,

Everybody said, "Rock 'N Roll is dead".

But it was only heaven bound.

Yeah, they thought it was over.

They felt left behind,

But oh it ain't the end of the line.

And the road goes on forever

And the light will always shine

And the song is never ending.

You will never reach the end of the line.